Figure 4 Non-PTA average growth in firm varieties if treated as if PTA member

Figure 5 Non-PTA export growth margins if treated as if PTA member

Going further, we then split our sample into industries that would face high or low tariffs in a trade war according to importer market power.6 In Figure 6, we find that the PTA export growth differentials were highest in the industries that faced high potential protection, whereas the differential is small if potential protection was low.

Figure 6 PTA export growth differential by high and low potential protection, measured by importer market power

A summary statistic that places the value of agreements into perspective is the foreign income growth differential required to offset the difference in US exports to non-PTA versus PTA markets from uncertainty. In 2011, closing the gap between the actual export growth and the PTA treatment counterfactual from Figure 5 is equivalent to cumulative foreign GDP growth from 2008-2011 of 5% for total exports, or 8% for the extensive margin.

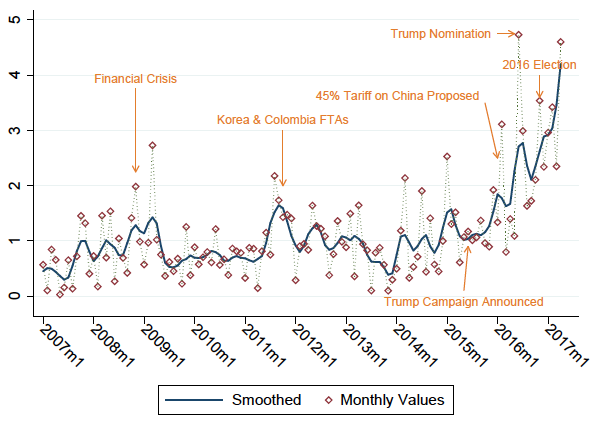

Broader implications: That was then, this is nowOur findings suggest the current network of trade agreements lowered joint policy and economic uncertainty, particularly in high potential protection industries. Back in 2008, the WTO Director General argued the WTO provides “[…] the everyday economy, with a collective insurance policy against the disorder caused by unilateral actions, whether open or disguised; a guarantee of security for transactions in times of crisis, henceforth an element of resilience that is vital to the running of a globalized world. In short, a global insurance policy for a global real economy”. Our findings highlight the insurance value of PTAs during the last economic crisis – a benefit that can’t be ignored in light of recent US threats of protectionism, the renegotiation of NAFTA, and Brexit. The importance of WTO membership is less clear, but is also under threat. It may become increasingly important if some PTAs are weakened or dissolved. Renegotiation of agreements is not necessarily bad. But if negotiating international policy under duress or exiting first and hoping to work out the details later becomes more common, the value of these agreements in the next crisis may be greatly diminished.

ReferencesBaker, S R, N Bloom, and S J Davis (2016), “Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(4): 1593–1636.

Bown, C P, and M A Crowley (2013), “Import protection, business cycles, and exchange rates: Evidence from the Great Recession”, Journal of International Economics 90(1): 50–64.

Bown, C (2018), “Trump’s Steel and Aluminum Tariffs: How WTO Retaliation Typically Works”, PIIE Blog, 5th March.

Broda, C, N Limão, and D E Weinstein (2008), “Optimal Tariffs and Market Power: The Evidence”, American Economic Review 98(5): 2032–65.

Carballo, J, K Handley, and N Limão (2018), “Economic and Policy Uncertainty: Export Dynamics and the Value of Agreements”, NBER Working Paper 24368.

Crowley, M, H Song, and N Meng (2016), “Tariff Scares: Trade policy uncertainty and foreign market entry by Chinese firms”, CEPR Discussion Paper no. 11722.

Handley, K (2014), “Exporting under trade policy uncertainty: Theory and evidence”, Journal of International Economics 94(1): 50–66.

Handley, K, and N Limão (2015), “Trade and Investment under Policy Uncertainty: Theory and Firm Evidence”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy (4).

Handley, K, and N Limão (2017a), “Policy Uncertainty, Trade, and Welfare: Theory and Evidence for China and the United States”, American Economic Review 107(9): 2731–83.

Handley, K, and N Limão (2017b), “Trade under T.R.U.M.P. policies”, in C P Bown (ed.), Economics and Policy in the Age of Trump, chapter 13, CEPR Press, London.

New York Times (2018), “E.U. Leader Threatens to Retaliate with Tariffs on Bourbon and Bluejeans”, 2 March.

Endnotes[1] The index applies the basic methodology in Baker et al. (2016) who focus on domestic policy uncertainty.

[2] Such tariffs can reduce US imports by over $14 billion and lead to unprecedented levels of retaliation (see Bown 2018).

[3] In Handley and Limão (2017a), we show that US TPU has high costs for its consumers’ welfare – a modest increase in the probability of high protection against all its partners is equivalent to 1/3 of the cost US consumers would face if imports were banned.

[4] This research was conducted while the authors were Special Sworn Status researchers at the Census HQ and Michigan Research Data Centers. Any opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Census Bureau. All results have been reviewed to ensure that no confidential information is disclosed.

[5] G20 Communique, April 2, 2009, see here, and G20 Leaders' Communique from the Hangzhou Summit, September 5, 2016, see here.

[6] Some goods are more responsive to trade barriers than others and a foreign government would increase tariffs more on the least responsive goods, i.e. those where its market power is high. See Broda et al. (2008) for some empirical evidence.

雷达卡

雷达卡

京公网安备 11010802022788号

京公网安备 11010802022788号