Empirical evidenceTo analyse whether this increased trade also caused growth, we exploit the fact that open sea sailing creates different levels of connectedness for different points on the coast. The shape of the coast and the location of islands determineshow easy it is to reach other points, which might be potential trading partners, within a certain distance. We create such a measure of connectedness for travel via sea. Figure 1 shows the values of this measure on a map and demonstrates how some regions, for example the Aegean but also southern Italy and Sicily, are much better connected than others.

We use this measure of connectedness as a proxy for trading opportunities.

Figure 1 Log connectedness at 500km distance

Note: Darker blue indicates better connected locations.

Measuring growth for an early period of human history is more difficult as we have no standard measure of income, GDP, or even population. We quantify growth by the presence of archaeologic sites for settlements or urbanisations. While this is clearly not a perfect measure, more sites should imply more human presence and activity. We then relate the number of active archaeological sites in a particular period to our measure of connectedness.

We find a large positive relationship between connectedness and archaeological sites. The effect of connections on growth in the Iron Age Mediterranean are up to twice as large as the effects Donaldson and Hornbeck (2016) found for US railroads. Although these results are unlikely to be directly comparable, the magnitudes suggest a large role for geography and trade in development even at such an early juncture in history.

When we repeat our analysis for different points in time, we find considerably smaller effects in the 2ndmillennium BC and then a sizable increase from 750 BC onward. While this is consistent with the increased trade activity during the Iron Age, we caution that the archaeological data for the earlier period are sparser and appear less reliable.

The effects of connections peak around 500 BC and then become weaker. The weakening of the effect of connectedness during the height of the Roman Empire, which stretched across the entire Mediterranean, may seem puzzling. It may be due to new settlements emerging between 900 BC and 500 BC being in the best-connected locations, while new cities later arose in worse-connected locations. We find some evidence for this while at the same time the best-connected cities persist. This is consistent with a large literature on the persistence of city locations (Davis and Weinstein 2002, Bleakley and Lin 2012, Bosker and Buringh 2017, Michaels and Rauch 2018 among others).

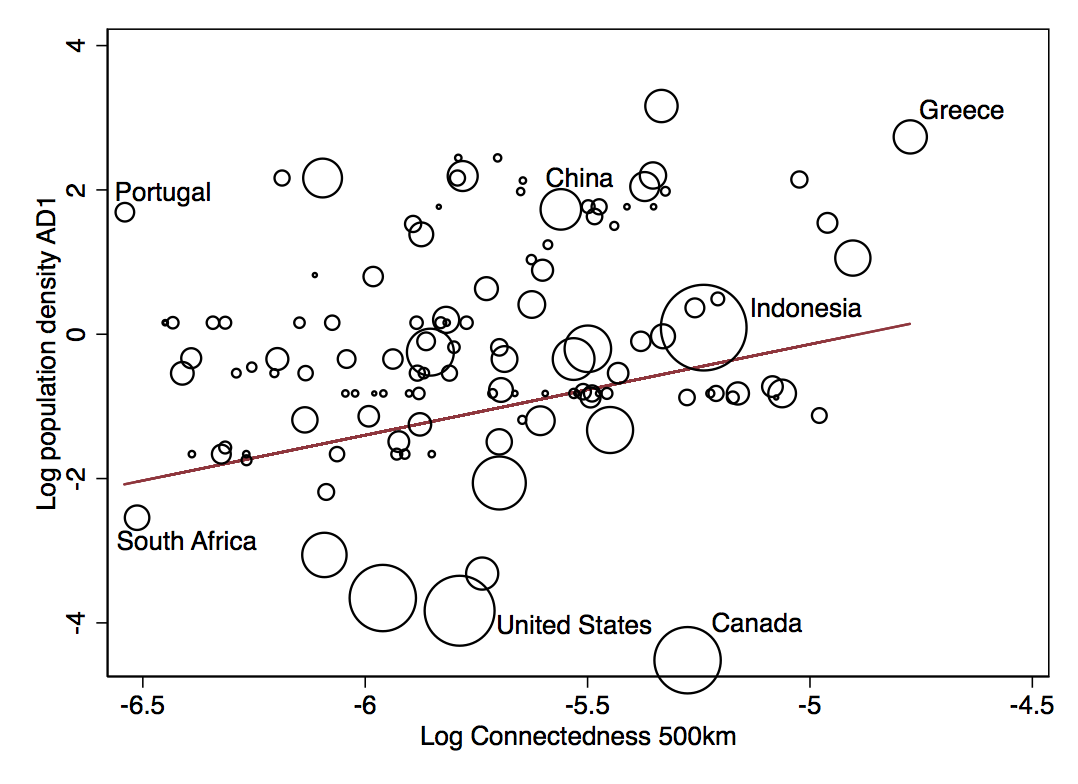

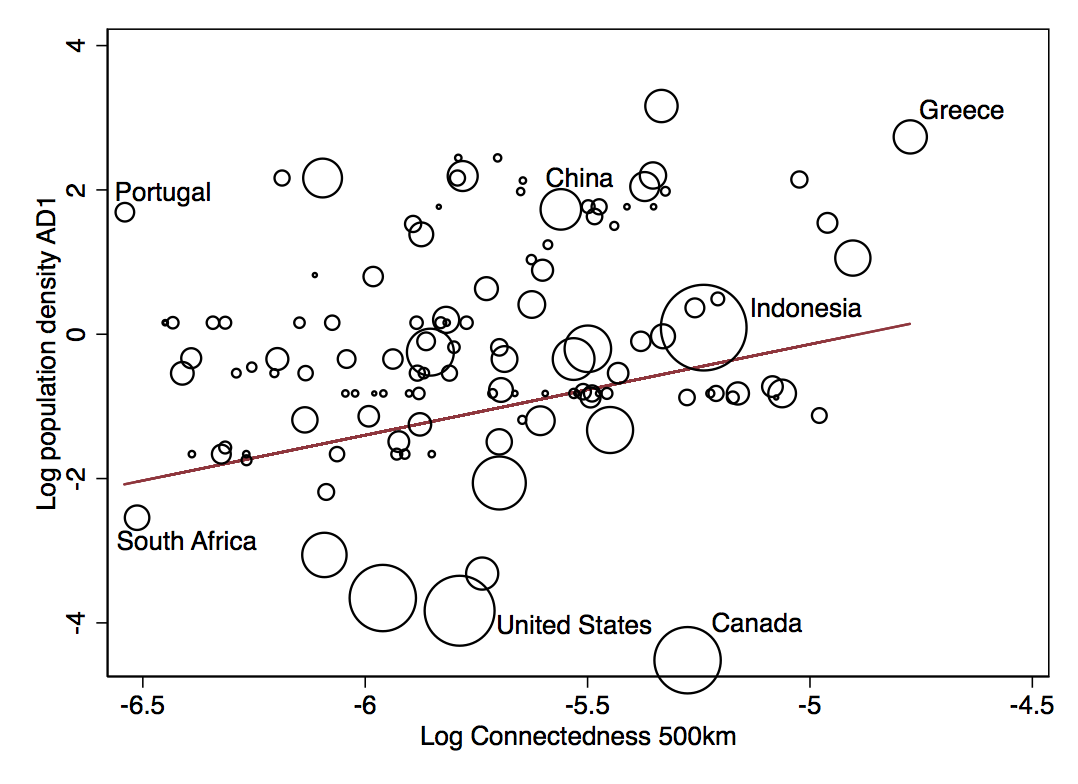

Not purely a Mediterranean phenomenonWhile we have the most systematic data on archaeological sites for the Mediterranean, we also explore whether we can find similar effects at a world scale. For this exercise we use a measure of population density in the year 1 AD, constructed by economic historians McEvedy and Jones (1978). This measure varies only at the level of modern countries, so we also aggregate connectedness to the country level. As Figure 2 shows, there is a strong positive relationship between a country’s average connectedness and its population density in year 1 AD as well.

Figure 2 Relationship between population density in 1 AD and connectedness

ConclusionsOur results suggest that connectedness and the associated trading opportunities matter for human development. Along the Mediterranean coast, there are more archaeological sites in locations that were better connected over sea, and this relationship emerges most strongly after 1000 BC, when open sea routes were travelled routinely and trade intensified. Once these locational advantages emerged, the favoured locations retained their urban developments over the following centuries.

ReferencesAcemoglu, D, S Johnson, and J Robinson (2005), “The Rise of Europe: Atlantic Trade, Institutional Change, and Economic Growth”, American Economic Review 95: 546-579.

Bakker, J D, S E Maurer, J-S Pischke, and F Rauch (2018), “Of Mice and Merchants: Trade and Growth in the Iron Age”, NBER working paper.

Bleakley, H and J Lin (2012), “Portage and Path Dependence”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127: 587-644.

Bosker, M, and E Buringh (2017), “City Seeds: Geography and the Origins of the European City System”, Journal of Urban Economics 98: 139-157.

Broodbank, C (2006), “The Origins and Early Development of Mediterranean Maritime Activity”, Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 19.2: 199-230.

Cucchi, T, J D Vigne, and J C Auffray (2005), “First Occurrence of the House Mouse (Mus musculus domesticus Schwarz & Schwarz 1943) in the Western Mediterranean: a Zooarchaeological Revision of Subfossil Occurences”, Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 84.3: 429-445

Davis, D and D Weinstein (2002), “Bones, Bombs, and Break Points: The Geography of Economic Activity”, American Economic Review 92: 1269-1289

Donaldson, D, and R Hornbeck (2016), “Railroads and American Economic Growth: a “Market Access” Approach”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 131: 799-858

Feyrer, F (2009), “Trade and Income--Exploiting Time Series in Geography”, NBER Working Paper 14910.

McEvedy, C, and R Jones (1978), Atlas of World Population History, Penguin Books.

Michaels, G (2008), "The effect of trade on the demand for skill: Evidence from the interstate highway system." The Review of Economics and Statistics 90(4): 683-701.

Michaels, G, and F Rauch (2018), “Resetting the Urban Network: 117-2012”, Economic Journal 128: 378-412.

Pascali, L (2017), “The Wind of Change: Maritime Technology, Trade and Economic Development”, American Economic Review 107: 2821-2854.

Redding, S J and D M Sturm (2008), “The Costs of Remoteness: Evidence from German Division and Reunification”, American Economic Review 98: 1766-97.

雷达卡

雷达卡

京公网安备 11010802022788号

京公网安备 11010802022788号