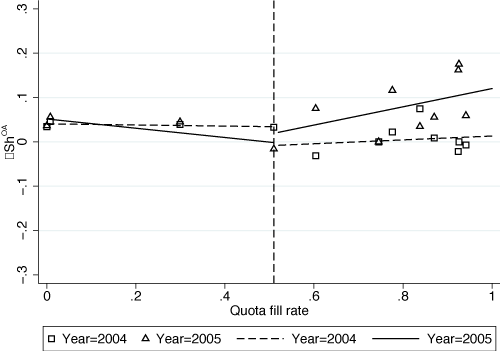

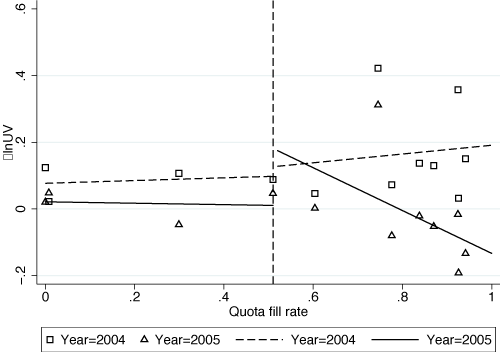

Figure 1 Change in provision of trade credit and prices before and after the end of the MFA

Notes: DShOA denotes the annual change in the share of exports on trade credit (OA terms). DlnUV denotes the annual change in the logarithm of unit values. In the left (right) panel, a marker represents average DShOA (DlnUV) over firms, products and destination countries for a given quota-fill rate and year. Lines represent fitted values of (unconditional) linear predictions. The vertical lines represent the quota fill rate of 0.5 as of 2004.

These patterns are consistent with the theoretical predictions that Turkish exporters affected by an increase in competitive pressures would respond by extending additional trade credit and lowering prices.

The regression analysis suggests that Turkey’s exports of MFA products affected by the shock saw a 4 percentage point larger increase in the share of sales on trade credit and a 7% larger decline in prices compared to the other MFA products destined for the EU market in the post-MFA period.

To investigate the interaction between the two margins of adjustment, we examine whether export flows with a high initial share of sales on trade credit experienced a larger subsequent fall in prices. A high share of sales on trade credit in the pre-shock period means less room to increase trade credit after the shock and hence less room to attenuate the necessary price response by switching financing terms. Our empirical findings are in line with this hypothesis. Export flows of affected products with no room for further adjustment on the financing side (i.e. full reliance on trade credit before the shock) experienced about 12% larger fall in prices relative to flows with no reliance on trade credit before the shock.

ConclusionsOur study has two implications. First, it highlights the importance of considering the full terms of the transaction, including the financing part, rather than just focusing on price effects, for a complete understanding of the effects of a competitive shock on firms. Second, our results rationalise why many governments are engaged in provision of trade financing by establishing import-export banks.

ReferencesAmiti, M and A K Khandelwal (2013), “Import competition and quality upgrading,” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2): 476-490.

Antràs, P and C F Foley (2015), “Poultry in motion: a study of international trade finance practices,” Journal of Political Economy, 123 (4): 809–852.

Bernard, A B, S J Redding and P K Schott (2010), “Multiple-product firms and product switching,” American Economic Review, 100 (1): 70–97.

Bernard, A B, S J Redding and P K Schott (2011), “Multiproduct firms and trade liberalization,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126 (3): 1271–1318.

Demir, B and B Javorcik (2018), “Don’t throw in the towel, throw in trade credit!,” Journal of International Economics, 111: 177-189.

Eckel, C and J P Neary (2010), “Multi-product firms and flexible manufacturing in the global economy,” Review of Economic Studies, 77 (1): 188–217.

Mayer, T, M J Melitz and G I P Ottaviano (2014), “Market size, competition, and the product mix of exporters,” American Economic Review, 104 (2): 495–536.

Schmidt-Eisenlohr, T (2013), “Towards a theory of trade finance,” Journal of International Economics, 91: 96–112.

U.S. Department of Commerce International Trade Administration (2012), Trade Finance Guide. A Quick Reference for U.S. Exporters.

雷达卡

雷达卡

京公网安备 11010802022788号

京公网安备 11010802022788号