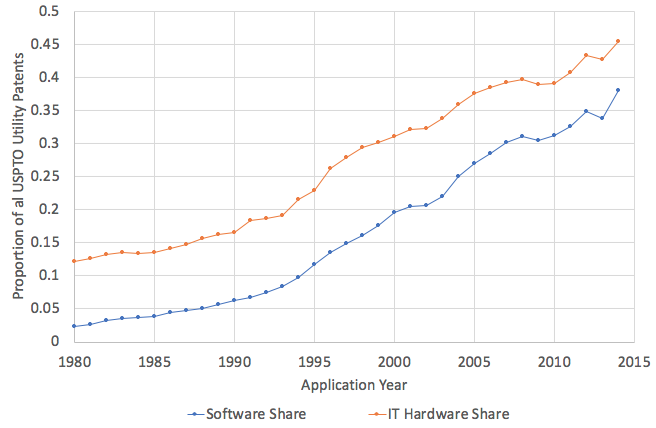

Conclusions and implicationsOur analysis suggests that the increasing reliance on IT and software in innovation, and the growing endowments of specialised human capital in countries like India and China, have induced US MNCs to conduct more R&D in these locations. This has important implications:

- It suggests that there is a constraint on the supply of IT and software human capital in the US, and that these human resource constraints limit the invention possibilities for US-based multinational firms, even for those firms in which innovative activity and technological opportunity seem to be at the highest levels.4

- Global flows of investment, people, and ideas can help relax these constraints through open immigration policies and liberal trade and FDI policies. When successful, these flows raise growth, productivity, and consumption possibilities around the world. When US multinationals are able to import talent or export R&D work to the regions in which talent resides, this reinforces US technological leadership. Conversely, politically engineered constraints on this response clearly undermines the competitiveness of US-based firms.

We do not directly explore the impact of immigration policy in our paper, but existing evidence suggests that the openness of the US’ labour market to immigrants in the 1990s allowed US-based firms to quickly adapt to the software-biased shift in technological opportunity. This created an unexpected and sharp increase in demand for software engineers, met at the height of the internet boom by importing more software engineers than the US was training in its own universities.5

Since the early 2000s, however, the US labour market has become more closed to immigration. Caps on high-skilled visas like the H-1B visa programme have grown more restrictive, and evidence from Glennon (2018) shows that these restrictive high-skilled immigration caps drove US MNCs to shift some high-skilled activity abroad in an effort to address these constraints.

Relatively liberal trade and FDI policies have allowed MNCs to address their human resource constraints by sourcing from abroad, but an open immigration regime for highly skilled workers would further ease this constraint.

- Finally, in addition to open immigration and liberal trade and FDI policies, the constraint on the supply of IT and software human capital in the US could be addressed with education policies that expand the supply of domestic IT and software human capital.

Authors' note: We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Science Foundation through two grants: 1360165 and 1360170. The statistical analysis of firm-level data on US multinational companies was conducted at the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), United States Department of Commerce under arrangements that maintain legal confidentiality requirements. The views expressed do not reflect official positions of the US Department of Commerce or the NSF.

ReferencesArora, A, L G Branstetter, and M Drev (2013), “Going Soft: How the Rise of Software-Based Innovation Led to the Decline of Japan’s IT Industry and the Resurgence of Silicon Valley”, Review of Economics and Statistics 95(3): 757–75.

Arora, A and A Gambardella, eds (2005a), From Underdogs to Tigers: The Rise and Growth of the Software Industry in Brazil, China, India, Ireland, and Israel, Oxford University Press.

Arora, A and A Gambardella (2005b), “The Globalization of the Software Industry: Perspectives and Opportunities for Developed and Developing Countries”, Innovation Policy and the Economy 5: 1–32.

Bloom, N, C Jones, J Van Reenen, and M Webb (2018), "Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find?", working paper, Stanford.

Bound, J, B Braga, J M Golden, and G Khanna (2015), “Recruitment of Foreigners in the Market for Computer Scientists in the United States”, Journal of Labor Economics 33(S1): S187–223.

Branstetter, L, B Glennon, and J B Jensen (2018a), “The IT Revolution and the Globalization of R&D”, in Innovation Policy and the Economy, Volume 19, edited by J Lerner and S Stern, University of Chicago Press.

Branstetter, L, M Drev, and N Kwon (2018b), “Get With the Program: Software-Driven Innovation in Traditional Manufacturing,” Management Science.

Glennon, B (2018),How Do Restrictions on High-Skilled Immigration Affect MNC Foreign Affiliate Activity?, working paper.

Jones, B (2009), "The Burden of Knowledge and the Death of the Renaissance Man: Is Innovation Getting Harder?" Review of Economic Studies 76(1): 283–317.

Kerr, S P and W R Kerr (2018), “Global Collaborative Patents”, The Economic Journal 128(612).

US Department of Homeland Security (2016), "Characteristics of H-1B Specialty Occupation Workers", Fiscal Year 2016 Annual Report to Congress.

Endnotes[1] Arora et al. (2013) presented evidence that superior access to software engineering human resources enabled US IT firms to out-innovate their Japanese rivals in the 1990s and 2000s. Branstetter et al. (2018b) found evidence that firms better positioned to exploit technological opportunities realise higher returns to their R&D investments.

[2] Classified using the industry of the foreign affiliate.

[3] National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, Survey of Earned Doctorates.

[4] This is consistent with research by Jones (2009) and Bloom et al. (2018), documenting the rising human resource requirements of innovation.

[5] Arora et al. (2013) argue that Japanese firms were constrained in their ability to respond to this shift, as a result of their rigid and closed-off labour market, and that part of Silicon Valley’s evident resurgence vis-à-vis their Japanese competitors was based on American firms’ greater access to immigrant talent.

雷达卡

雷达卡

京公网安备 11010802022788号

京公网安备 11010802022788号