Explaining the regional lag in wages and employment growthWe investigate several explanations that could potentially rationalise these surprising findings, and find empirical support for a mechanism involving a lack of inter-regional labour mobility, the slow movement of capital (the machines and buildings that workers use in production) between regions, and slow changes in local productivity driven by agglomeration economies (described below).

1. Geographic mobilityAlthough Brazil has a relatively high rate of geographic mobility, the labour market effects we document were not accompanied by systematic migration toward more favorably affected locations. Instead, workers in harder-hit locations adjusted primarily by transitioning to informal jobs in the same region.

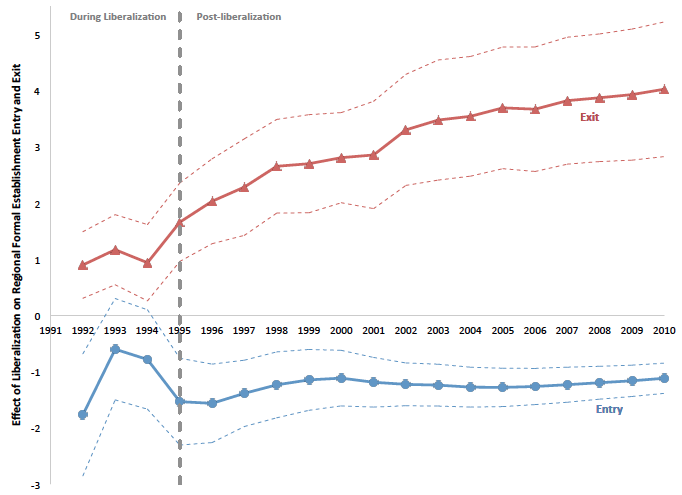

2. Movement of capitalCapital slowly reallocated away from badly shocked locations – existing machines and structures slowly depreciated, and investment in new capital was quickly redirected toward more favorably affected markets. Figure 3 illustrates that firm exit increased very gradually following liberalisation, and that investment (measured as firm entry) responded almost immediately and permanently.

Figure 3 Effect of liberalisation on regional formal establishment entry and exit

As suggested by Dix-Carneiro (2014), the slow reallocation of capital led to a steady amplification of the initial local labour demand shock, making workers in harder hit regions even less productive over time compared to those in more favorably affected regions.

3. Local productivityOur empirical analyses also suggest that agglomeration economies amplify the labour market effects of trade liberalisation; as firms in harder-hit regions leave the market, the productivity of remaining local firms gradually declines, further reducing local wage and employment growth.

Using a simple model of local labour markets, we show that capital reallocation and agglomeration economies together can explain the quantitative scale of the wage and employment effects that we document.

ImplicationsThese results have important implications for our thinking about the labour market effects of trade:

- The adjustment process triggered by trade can be much longer than previously anticipated, with regions facing larger tariff declines experiencing very long periods of depressed growth in earnings and employment.

- The magnitudes of the long-run regional effects are much larger than the short- or medium-run effects reported in prior research.

- When predicting the effects of increased trade or designing policies to help labour markets adjust to large shifts in the competitive landscape, it is essential to understand how capital adjusts across regions and how it interacts with workers in the labour market.

Our work shows that regions facing larger tariff reductions lag behind other regions in terms of wage and employment growth for many years, and these gaps are much larger than previously realised. These large and persistent differences should motivate further research aimed at determining effective policy responses that will help workers in different regions share more equally in the benefits of freer trade.

Photo credit: Marcelo Horn/Getty.

ReferencesAutor, D, Dorn, D and Hanson, G (2013), “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States”, American Economic Review 103(6): 2121-2168.

Dix-Carneiro, R (2014), “Trade Liberalization and Labor Market Dynamics,” Econometrica 82(3).

Dix-Carneiro, R and Kovak, B K (2017a), “Trade Liberalization and Regional Dynamics”, American Economic Review (forthcoming).

Dix-Carneiro, R and Kovak, B K (2017b), “Margins of Labor Market Adjustment to Trade”, NBER Working Paper No. 23595.

Kovak, B (2013), “Regional Effects of Trade Reform: What is the Correct Measure of Liberalization?”, American Economic Review 103(5): 1960–1976.

Stolper, W F and Samuelson, P A (1941), “Protection and Real Wages”, Review of Economic Studies 9(1): 58–73.

Topalova, P (2007), "Trade Liberalization, Poverty, and Inequality: Evidence from Indian Districts", in A Harrison (ed.), Globalization and Poverty, University of Chicago Press, pp. 291–336.

Endnotes[1] In a follow up paper (Dix-Carneiro and Kovak 2017b), we use alternative data to examine the effects of trade liberalisation on the informal labour market.

Rafael Dix-Carneiro

Rafael Dix-Carneiro Brian Kovak

Brian Kovak 扫码

扫码 京公网安备 11010802022788号

论坛法律顾问:王进律师

知识产权保护声明

免责及隐私声明

京公网安备 11010802022788号

论坛法律顾问:王进律师

知识产权保护声明

免责及隐私声明