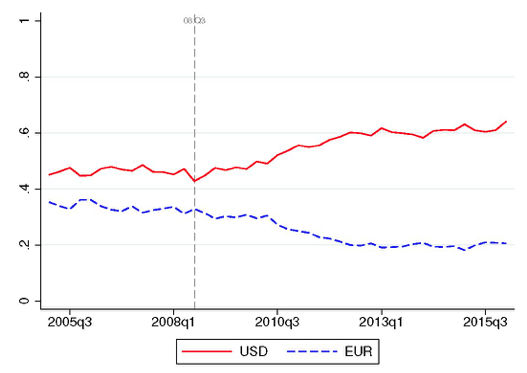

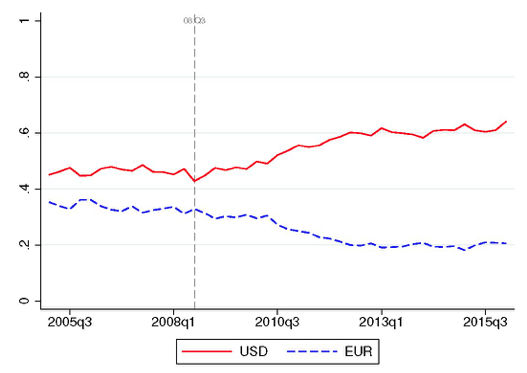

While the dollar has played a central role in the global economy since at least Bretton Woods, we uncover a striking trend in the dollar’s use that emerged in the last decade. As shown in Figure 1, whereas the euro and dollar were used to denominate comparable shares of cross-border corporate bond portfolios in our data during 2005–2007, the dollar’s share surged and the euro’s collapsed since the global and euro area crises of 2008–2010.

Figure 1 Share of cross-border corporate bond holdings in dollars and euros

A growing literature is developing models of competing international currencies (Farhi and Maggiori 2018, He et al. 2018, Stein and Gopinath 2018), and should aim to elaborate on the cause of this shift, whether due to uncertainty about the euro’s future or the increased benefit of holding dollar assets (as collateral, due to liquidity, or otherwise).

Our work shows that the currency of denomination of assets deserves more attention in international macroeconomics than has been the case thus far. Academics, investors, and policymakers alike should take note of how international currency status can change rapidly because of the important implications such a change can carry for the global allocation of capital.

ReferencesBoermans, M A and R Vermeulen (2016), “Newton meets Van Leeuwenhoek: Identifying international investors? Common currency preferences”, Finance Research Letters 17: 62–62.

Burger, J D, F E Warnock and V C Warnock (2017), “Currency matters: Analyzing international bond portfolios”, NBER, Working paper 23175.

Coeurdacier, N and P-O Gourinchas (2016), “When bonds matter: Home bias in goods and assets”, Journal of Monetary Economics 82: 119–137.

Engel, C and A Matsumoto (2009), “The international diversification puzzle when goods prices are sticky: It’s really about exchange-rate hedging, not equity portfolios”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 1(2): 155–188.

Farhi, E and M Maggiori (2018), “A model of the international monetary system”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(1): 295–355.

French, K R and J M Poterba (1991), “Investor diversification and international equity markets”, American Economic Review 81(2): 222–226.

Gopinath, G and J Stein (2018), “Banking trade, and the making of a dominant currency,” NBER, Working paper 24485.

He, Z, A Krishnamurthy and K Milbradt (2018), “A model of safe asset determination”, American Economic Review, forthcoming.

Maggiori, M, B Neiman and J Schreger (2018), “International currencies and capital allocation”, NBER, Working paper 24673.

Van Wincoop, E and F E Warnock (2010), “Can trade costs in goods explain home bias in assets?” Journal of International Money and Finance 29(6): 1108–1123.

Endnotes[1] Consistent with this, Burger et al. (2017) found, using TIC data, that US foreign investment across destination countries does not appear home-country-biased in the subset of debt that is dollar-denominated, and suggested it might apply more generally across countries and debt markets. See also Boermans and Vermeulen (2016).

[2] We emphasise that, while some mechanisms discussed in the literature can generate home-currency bias (Van Wincoop and Warnock 2010, Engel and Matsumoto 2009, Coeurdacier and Gourinchas 2016), they alone will not generate such a skewed allocation of capital across borrowers. Rather, the logic laid out in those papers would leave cross-firm lending undistorted, with investors simply using forward contracts or other derivatives to undo any undesired currency exposures found in their overall portfolios.

雷达卡

雷达卡

京公网安备 11010802022788号

京公网安备 11010802022788号