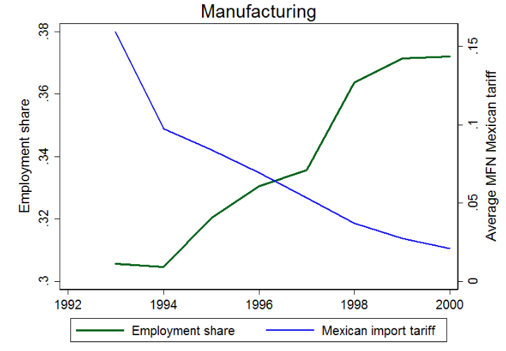

Trade liberalisation and informality within tradable sectorsTo study the relationship between Mexican trade liberalisation and the probability of holding a formal job for men and women, we use individual data from the Mexican labour force survey, the Encuesta Nacional de Empleo Urbano (ENEU), and data on Mexican import tariffs on US products. Our findings show that workers employed in an industry that experienced the average reduction in tariffs of 14% are 2% more likely to hold a formal job than workers in an industry facing no tariff reduction. Within sectors, firm characteristics matter. First, workers are more likely to hold formal jobs in large firms. This is in line with the literature on firms and informality, which shows that informal firms tend to be smaller (see La Porta and Shleifer 2014 among others). Second, the effect of trade policy reforms depends on a firm’s size. Considering trade liberalisation in Argentina, Cruces et al. (2017) find that industries with a large share of employment concentrated in small firms experience an increase in informality. We complement their analysis using individual data and find that a reduction in the sectoral tariff increases the probability of holding a formal job only in firms with more than 50 employees, and that this formalisation effect increases with firm size. This finding may be explained by a reallocation of employment towards bigger trade-oriented firms within sectors. Indeed, trade-oriented firms tend to be more intensive in formal jobs (Nataraj 2011, McCaig and Pavcnik 2015).

Trade liberalisation and informality in local labour marketsA recent but growing body of work has shown that international trade has different effects across regions within a country because of different industry mixes across regions. We additionally exploit the fact that men and women work in different industries within regions, and compute gender-specific regional exposure to trade liberalisation.

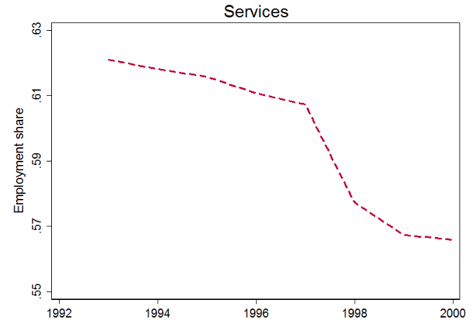

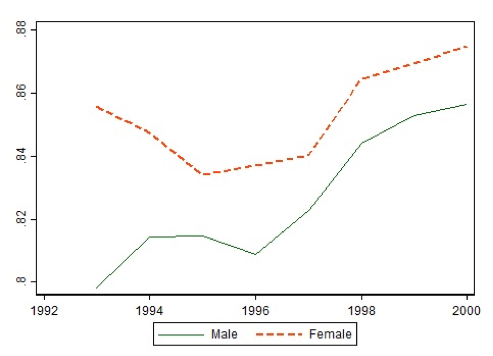

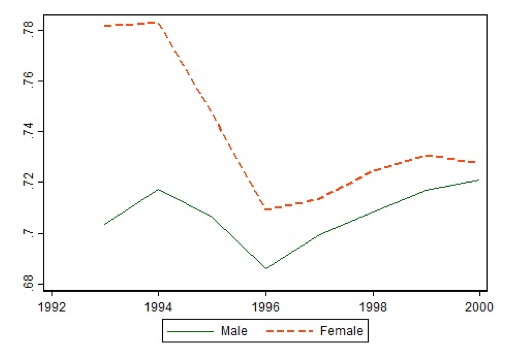

Exploiting yearly variation in tariffs between 1993 and 2001, we show that regional exposure to Mexican tariff reductions lead to an increase in the probability of formal employment for both men and women in the tradable sectors, and the effect is larger for men. However, results differ when we consider the non-tradable sectors. Indeed, women employed in a non-tradable industry in a region exposed to a strong reduction in tariffs have been lesslikely to hold a formal job than women working in a non-tradable industry in a region facing no reduction in tariffs.

To interpret the finding that the probability of holding a formal job has increased more for men than for women, we use a multi-sector Ricardo-Viner model with female and male labour, and formal and informal jobs. In this context, trade liberalisation leads to a greater increase male formal employment share relative to female formal employment share if comparative advantage sectors are intensive in formal labour, and if male labour is relatively more substitutable for capital than female labour.

Our results differ from those in Dix-Carneiro and Kovak (2017), who find that Brazilian micro-regions more exposed to tariff reductions experienced an increase in informality even 20 years after the trade reform. Nevertheless, our results seem in line with Atkin (2016), who documents a formal employment boom in Mexican export-oriented manufacturing industries over the 1990s. Moreover, export-oriented sectors benefited from the fall in Mexican tariffs as intermediate inputs became cheaper. Indeed, Mexican exports to the US use a very high share of US inputs (de Gortari 2017). Menezes-Filho and Muendler (2011) find for Brazil that lower intermediate-input tariffs are associated with lower odds of transitions into unemployment and out of the labour force, resulting in significantly more transitions into formality. However, reductions in product-market tariffs have opposite effects. This suggests that country differences in global supply-chains may be partially responsible for differing effects of import tariff reductions on formal employment across countries.

ConclusionOur findings show that trade liberalisation has heterogeneous effects on the likelihood of formal employment. First, within tradable sectors, we find that only workers employed in large firms experience an increase in the probability of holding a formal job with tariff reductions. Second, tradable and non-tradable sectors are affected in different ways, and it seems relevant to account for the potential employment reallocation and spillovers across sectors. Third, men and women face different exposure to trade liberalisation and therefore the formal employment response to trade policy reforms varies across gender. While the probability of formal employment increases in tradable sectors, especially for men, women are more likely to hold an informal job in non-tradable sectors.

ReferencesAtkin D (2016), “Endogenous Skill Acquisition and Export Manufacturing in Mexico”, American Economic Review, 106 (8), 2046-85.

Ben Yahmed, S, and P Bombarda (2018), “Gender, Informal Employment and Trade Liberalization in Mexico”, ZEW Discussion Paper No. 18-028.

Cruces, G, G Porto, and M Viollaz (2017), “Trade Liberalization and Informality in Argentina: Exploring the Adjustment Mechanisms”, mimeo.

de Gortari, A (2017), “Disentangling Global Value Chains”, mimeo.

Dix-Carneiro, R, and B Kovak (2017), “Trade liberalization and regional dynamics”, American Economic Review, 107 (10), 2908-2946.

Iacovone, L, and B Javorcik (2010), “Multi-product Exporters: Product Churning, Uncertainty and Export Discoveries”, Economic Journal, 120 (544) 481-499.

Juhn, C, G Ujhelyi, and C Villegas-Sanchez (2014), “Men, Women, and Machines: The Impact of Trade on Gender Inequality”, Journal of Development Economics, 106, 179-193.

La Porta, R, and A Shleifer (2014), “Informality and Development”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28 (3), 109-126.

McCaig, B, and N Pavcnik (forthcoming), “Export Markets and Labor Allocation in a Poor Country”, American Economic Review.

McCaig, B, and N Pavcnik (2015), “Informal Employment in a Growing and Globalizing Low-Income country”, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 105 (5), 545-50.

Menezes-Filho, N A, and M Muendler (2011), “Labor Reallocation in Response to Trade Reform”, NBER Working Paper 17372.

Nataraj, S (2011), “The Impact of Trade Liberalization on Productivity: Evidence from India's Formal and Informal Manufacturing Sectors”, Journal of International Economics, 85 (2), 292-301.

雷达卡

雷达卡

京公网安备 11010802022788号

京公网安备 11010802022788号